Comparto este interesante escrito de la historiadora Heather Cox Richardson analizando el desarrollo económico de los Estados Unidos en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. El objetivo de la Dr. Cox es demostrar la falsedad del «viejo tropo de que los demócratas no manejan la economía tan bien como los republicanos.»

Cox Richardson trabaja en Boston College y es autora, entre otros libros, de To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party (2014) y How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America (2020). Este trabajo fue publicado en su blog, Letters from America, dedicado a analizar la situación política y social estadounidensedesde una perspectiva histórica.

Heather Cox Richardson

Letter from an American

Solo por diversión, porque hoy se siente como un buen día para hablar sobre Grover Cleveland….

La economía ha crecido bajo el presidente Joe Biden, poniendo la mentira al viejo tropo de que los demócratas no manejan la economía tan bien como los republicanos.

Esto no debería sorprender a nadie. La economía ha tenido un mejor desempeño bajo los demócratas que los republicanos desde al menos la Segunda Guerra Mundial. CNN Business informa que desde 1945, el Standard & Poor’s 500, un índice de mercado de 500 compañías líderes que cotizan en bolsa en Estados Unidos, ha promediado una ganancia anual del 11.2% durante los años en que los demócratas controlaban la Casa Blanca, y una ganancia promedio del 6.9% bajo los republicanos. En el mismo período de tiempo, el producto interno bruto creció en un promedio de 4.1% bajo los demócratas, 2.5% bajo los republicanos. El crecimiento del empleo también es significativamente más fuerte bajo los demócratas que bajo los republicanos.

“Ha sido un patrón marcado en los Estados Unidos durante casi un siglo”, escribió David Leonhardt del New York Times el año pasado, “La economía ha crecido significativamente más rápido bajo los presidentes demócratas que los republicanos”.

La persistencia del mito de que los demócratas son malos para la economía es un ejemplo interesante de la resistencia de la retórica política sobre la realidad.

Comenzó en los años de la posguerra: los años posteriores a la Guerra Civil, es decir. Antes de la Guerra Civil, los hombres adinerados tendían a apoyar a los demócratas, ya que el gran dinero en el país estaba en las empresas de algodón de los principales esclavizadores en el sur de Estados Unidos, y expresaban su poder político a través del Partido Demócrata, que prometía proteger y nutrir la institución de la esclavitud humana. De hecho, cuando los soldados de la Confederación dispararon contra Fort Sumter en el puerto de Charleston, Carolina del Sur, en abril de 1861, no estaba claro en absoluto si los banqueros de la ciudad de Nueva York respaldarían a los Estados Unidos o a los rebeldes del sur. Después de todo, el Sur era la región más rica del país, y el Norte acababa de sufrir el devastador Pánico de 1857. Los líderes del sur se rieron de que sin el sur, los norteños morirían de hambre.

Las políticas económicas de los años de guerra, incluyendo nuestro primer dinero nacional, impuestos nacionales, universidades estatales y gasto deficitario, crearon un norte industrial en auge, pero muchos hombres adinerados resentían las políticas republicanas que sentían que ofrecían demasiado a los estadounidenses pobres (la Ley Homestead era una espina especial en sus costados porque significaba que las tierras occidentales tomadas de los indígenas estadounidenses ya no se venderían para traer dinero al Tesoro, sino que serían regalado a los agricultores pobres). Cuando el gobierno estableció bancos nacionales, estableciendo regulaciones sobre la lucrativa industria bancaria, los banqueros estatales estaban descontentos.

Si los hombres adinerados se mantendrían leales a Lincoln en 1864 era una pregunta abierta. Al final, lo hicieron, pero su lealtad después de la guerra estaba en juego.

Las políticas financieras de posguerra de los demócratas llevaron a los hombres adinerados a dar su lealtad al Partido Republicano. Ansiosos por hacer incursiones en la popularidad de los republicanos, los demócratas del norte señalaron que las ganancias económicas de los años de guerra habían ido a parar a los que estaban en la cima de la economía, y pidieron políticas financieras que nivelaran el campo de juego. En particular, querían pagar los intereses de la deuda de guerra con billetes verdes en lugar de oro, lo que haría que los bonos fueran significativamente menos valiosos. La alteración también establecería que los partidos políticos podrían asumir el cargo y cambiar los compromisos financieros del gobierno después de que ya estuvieran en vigor.

Los republicanos reconocieron que si un cambio de este tipo fuera legítimo, la capacidad del gobierno para pedir prestado en el futuro, por ejemplo, para sofocar otra rebelión, se vería obstaculizada. Estaban tan preocupados que en 1868, protegieron la deuda en la propia Decimocuarta Enmienda, diciendo: “La validez de la deuda pública de los Estados Unidos, autorizada por la ley, incluidas las deudas incurridas para el pago de pensiones y recompensas por servicios en la represión de la insurrección o la rebelión, no será cuestionada”.

Cuando parecía que una coalición que incluía a los demócratas podría ganar la presidencia en 1872, los líderes de Wall Street apoyaron públicamente a los republicanos y, a cambio, los republicanos se retiraron de apoyar a los trabajadores que habían formado su base de votantes inicial.

Los supremacistas blancos del sur habían comenzado a señalar que permitir que los hombres pobres votaran conduciría a una redistribución de la riqueza, ya que votaron por carreteras, escuelas y hospitales que solo podían pagarse con impuestos a quienes tenían propiedades. Tal sistema era, acusaron, “socialismo”.

Mientras que los blancos del sur dirigían su animosidad hacia sus vecinos negros anteriormente esclavizados, los norteños de medios adoptaron sus ideas y lenguaje, pero atacaron a los inmigrantes y trabajadores organizados. Si esas personas llegaran a controlar el gobierno y, por lo tanto, la economía, argumentaron los estadounidenses más ricos, traerían el socialismo a Estados Unidos y la nación nunca se recuperaría.

Mientras que los blancos del sur dirigían su animosidad hacia sus vecinos negros anteriormente esclavizados, los norteños de medios adoptaron sus ideas y lenguaje, pero atacaron a los inmigrantes y trabajadores organizados. Si esas personas llegaran a controlar el gobierno y, por lo tanto, la economía, argumentaron los estadounidenses más ricos, traerían el socialismo a Estados Unidos y la nación nunca se recuperaría.

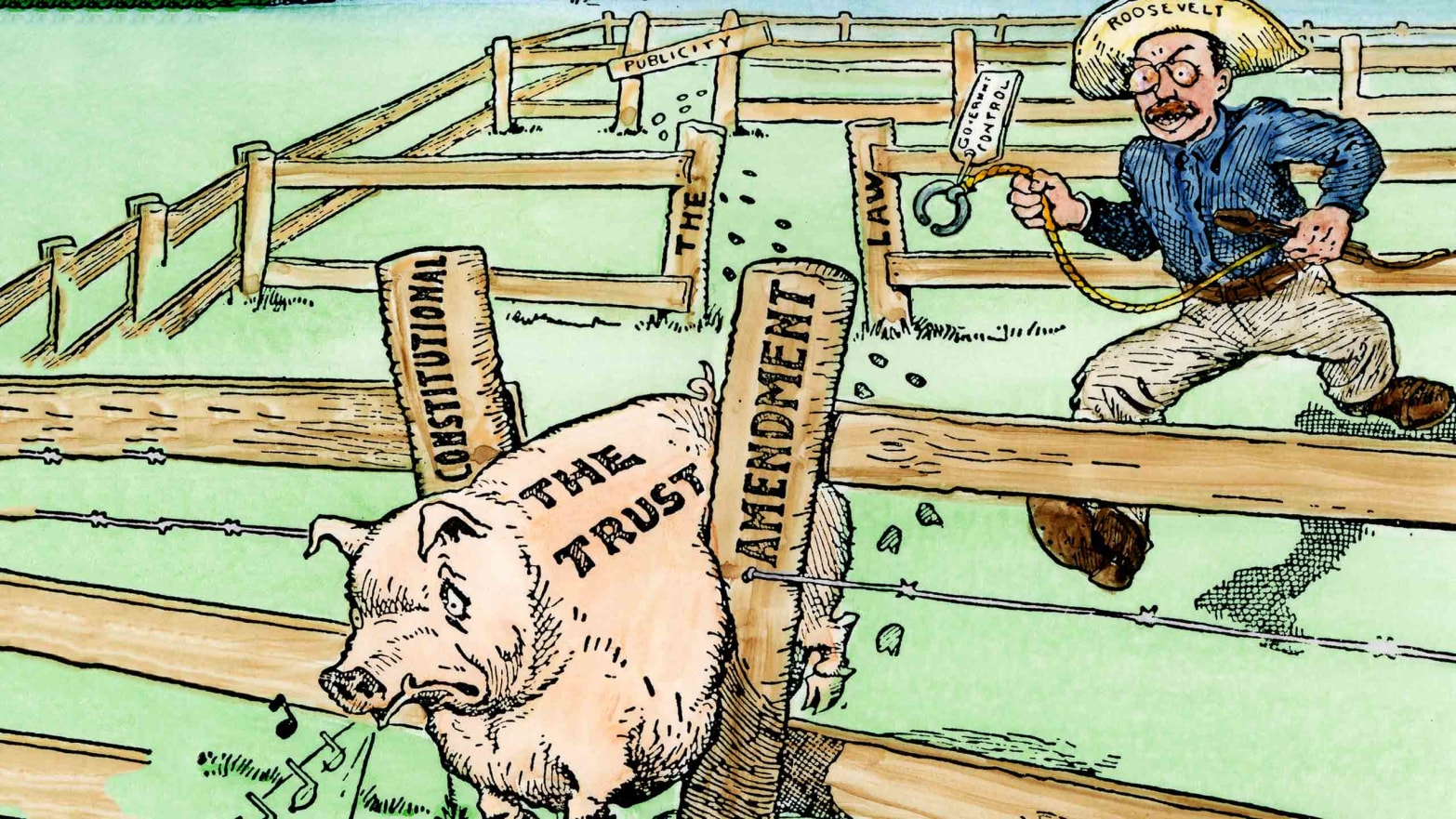

Cada vez más, el poder se trasladó a los industriales ricos que, después de 1872, fueron representados por el Partido Republicano. Exigieron aranceles altos que protegieran a sus industrias al mantener fuera la competencia extranjera y, por lo tanto, les permitieran confabularse para aumentar los precios a los consumidores. En la década de 1880, los senadores republicanos estaban sirviendo abiertamente a las grandes empresas; incluso el acérrimo republicano Chicago Tribune se lamentó en 1884 de que “cada uno de la mitad de los miembros portentosos y bien vestidos del Senado se pueden ver los contornos de alguna corporación interesada en obtener o impedir la legislación”.

A medida que el dinero se movía a la cima de la economía, los demócratas retrocedieron, pidiendo al gobierno que restableciera la igualdad de condiciones entre los trabajadores y sus empleadores. Mientras lo hacían, los republicanos aullaron que los demócratas abogaban por el socialismo.

Finalmente, después de la administración espectacularmente corrupta del republicano Benjamin Harrison, que los empresarios habían llamado “sin lugar a dudas la mejor administración de negocios que el país haya visto”, sucedió lo impensable. En las elecciones de 1892, por primera vez desde la Guerra Civil, los demócratas tomaron el control de la Casa Blanca y el Congreso. Prometieron controlar el poder de las grandes empresas reduciendo los aranceles y aflojando la oferta monetaria. Esto, insistieron los republicanos, significaba la ruina financiera.

Los republicanos advirtieron que el capital huiría de los mercados e instaron a los inversores extranjeros, de quienes dependía la economía, a llevarse su dinero a casa. Predijeron una crisis financiera cuando los demócratas abrazaron el socialismo, el anarquismo y la organización laboral. El dinero fluyó fuera del país cuando la administración saliente de Harrison echó gasolina al fuego de los temores de los medios y se negó a actuar para tratar de cambiar el rumbo. El secretario del Tesoro de Harrison, Charles Foster, dijo que su trabajo era solo “evitar una catástrofe” hasta el 4 de marzo, cuando el presidente demócrata Grover Cleveland asumiría el cargo.

Grover Cleveland

No lo logró del todo. El fondo cayó de la economía el 17 de febrero, cuando la Reading Railroad Company no pudo hacer su nómina, lo que provocó un pánico en todo el país. El mercado de valores se derrumbó. Y, sin embargo, la administración Harrison se negó a hacer nada hasta el día en que Cleveland asumió el cargo, cuando Foster anunció amablemente que el Tesoro “estaba en la base”.

A Cleveland cayó el pánico de 1893, con sus huelgas, marchadores y desesperación, todo lo cual los opositores insistieron en que era culpa de los demócratas. En las elecciones de mitad de período de 1894, los republicanos mostraron las estadísticas de los primeros dos años de Cleveland y dijeron a los votantes que los demócratas destruyeron la economía. Los votantes podrían restaurar la salud de la economía de la nación eligiendo a los republicanos nuevamente. En 1894, los votantes devolvieron a los republicanos el control del gobierno en el mayor deslizamiento de tierra de mitad de período en la historia de Estados Unidos, y la imagen de los demócratas como malos para la economía se consolidó.

A partir de entonces, los republicanos retrataron a los demócratas como débiles en la economía. Cuando el siguiente presidente demócrata en asumir el cargo, Woodrow Wilson, socavó el arancel tan pronto como asumió el cargo, reemplazándolo con un impuesto sobre la renta, los opositores insistieron en que la Ley de Ingresos de 1913 estaba inaugurando la caída socialista del país. Cuando el presidente demócrata Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) fue pionero en el New Deal, los republicanos vieron el socialismo. Durante el siglo pasado, esa retórica solo se ha fortalecido.

Y, sin embargo, por supuesto, han sido las políticas económicas republicanas las que abrieron la posibilidad de que los demócratas prueben nuevos enfoques de la economía, para que sirva a todos los estadounidenses, en lugar de a unos pocos favorecidos. Como dijo FDR: “Es de sentido común tomar un método y probarlo: si falla, admítelo con franqueza y pruebe otro. Pero sobre todo, prueba algo. Los millones de personas que están en situación de necesidad no se quedarán quietos para siempre mientras las cosas para satisfacer sus necesidades estén al alcance de la mano”.

Al final, eso es lo que los economistas entrevistados por Leonhardt el año pasado piensan que está detrás de la capacidad de los demócratas para administrar la economía mejor que los republicanos. Los republicanos tienden a aferrarse a teorías abstractas sobre cómo funciona la economía , teorías sobre altos aranceles o recortes de impuestos, por ejemplo, que tienden a concentrar la riqueza hacia arriba – mientras que los demócratas son más pragmáticos, dispuestos a prestar atención a los hechos en el terreno y a las lecciones históricas sobre lo que funciona y lo que no.

Notas:

https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2019/business/stock-market-by-president/index.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/02/opinion/sunday/democrats-economy.html

Traducido por Norberto Barreto Velázquez